In my last post, I introduced Shai-Hulud, a sophisticated supply chain attack that exploited lifecycle scripts in npm packages to compromise developer environments. I also shared how I secured my development environment with two critical defenses: disabling package scripts globally and isolating everything in dev containers. In this post, I’ll walk you through the additional layers of defense that I implemented to protect myself against this and future attacks.

Defense layer 3: Require signed commits

One of the more subtle risks in a supply chain attack is that malicious code might commit changes to your repository. This could be part of a multi-stage attack where the first payload just modifies your codebase to include a backdoor, then disappears. By requiring signed commits, you make this much harder.

A signed commit provides a cryptographic guarantee that the commit was created by a specific user and hasn’t been altered. By requiring some level of user interaction to sign commits, you block attempts to create a new commit without your knowledge. In my case, I use 1Password as my signing key provider, which adds several layers of protection:

External credential storage

The signing key never touches my filesystem. It lives in 1Password’s secure vault, which means even if a malicious script gets access to my home directory, it can’t steal my signing key.

Biometric authentication

Every time I sign a commit, 1Password requires biometric authentication to access the key. This prevents scripts from creating commits without my explicit approval. For convenience, the approval can be remembered for a short period of time to strike a balance between security and usability.

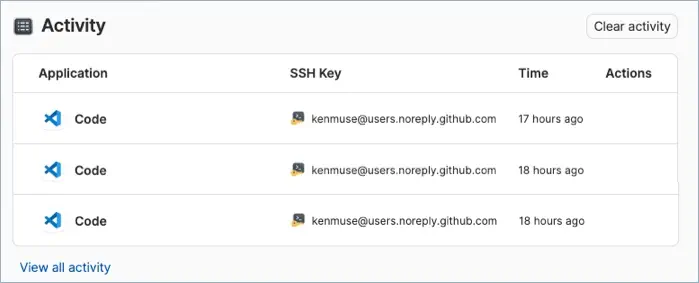

Activity logging

1Password records every time my signing key is used, showing me the application, timestamp, and purpose. If something unexpected happens, I can see it in the activity log.

It’s not just 1Password

You don’t have to use 1Password to make this work. Ultimately, this is creating a step that requires user interaction whenever I attempt to write a commit to my repository. You could achieve similar protections using GPG keys. Requiring the user to enter a passphrase to unlock the key adds a layer of interaction and protection. The key to making this work is ensuring that your .gitconfig is set up to sign all commits automatically. GitHub provides

documentation on how to configure commit signing, including the steps for

configuring Git signing by default.

You can also consider a hardware device that stores your signing keys and requires physical interaction, such as a YubiKey. Hardware devices are a great option if you’re not using a dev container. Unfortunately, using this with dev containers can be challenging – you may need USB/IP to expose USB devices to containers on Windows and macOS machines.

Related GitHub settings

You can also enforce signed commits in your repository settings on GitHub, ensuring that even if you somehow bypass your local configuration, unsigned commits will be rejected. This prevents unauthorized changes from entering your codebase. Of course, this is just one of several settings in GitHub that help secure your repository.

Defense layer 4: Repository configuration

The final layer of defense happens at the repository level. By requiring pull requests for all changes and enforcing status checks, you create a checkpoint where automated security scans can catch malicious code before it reaches your main branch.

Configure repository rulesets

GitHub now uses rulesets as the modern approach to enforcing branch protections. Rulesets are more flexible and powerful than the older branch protection rules, and they can apply to multiple branches or even tags.

In your GitHub repository settings, create a ruleset for your main branch (or use an organization-level ruleset to apply consistent policies across repositories):

- Require pull requests before merging

- Require status checks to pass before merging

- Require at least one (and preferably two) approvers for pull requests

- Do not allow bypassing of pull request requirements

This configuration ensures that no code can reach your main branch without going through a review process. Automated security scans (like Dependabot, CodeQL, or third-party tools) can also run as part of the pull request checks to catch vulnerabilities before you merge them.

Custom images

If your organization uses GitHub Actions, you can now use

custom runner images with larger hosted runners. This allows you to secure the environment for your workflow. For example, you can include system .npmrc and .yarnrc.yml files that disable package scripts, ensuring that even if a workflow checks out untrusted code, it cannot execute malicious lifecycle scripts by default.

In some cases, it might even make sense for the image to incorporate a secured, pre-configured cache of specific packages or binaries. This way, the workflow does not need to reach out to the public package registry at all, further reducing the attack surface.

Use environment protection rules

If you’re accessing external systems without using environments, you might be sacrificing an important security control. Environments allow you to define rules (and automated controls) that determine whether a workflow can access secrets or deploy to sensitive systems. This includes support for manual reviews, wait timers, and restricting access to specific branches or tags. Until the workflow passes these checks, it can’t access the secrets needed to reach external systems.

This can be combined with

OIDC, to create a strong security boundary without needing to expose any passwords or long-lived credentials. If you’re using Azure, consider the

flexible federated identity credentials preview, which lets you define fine-grained approval of a request based on the sub and job_workflow_ref claims. Why is job_workflow_ref valuable? It includes the workflow file and ref (branch or tag) that triggered the request, allowing you to restrict access only to specific workflows within a given repository. Terraform and GitLab are also supported.

Avoid pull_request_target

Like many other exploits, the Shai-Hulud attack is thought to have started by exploiting a workflow that used the pull_request_target trigger. Unlike the regular pull_request trigger, this trigger can allow a forked repository access to secrets and elevated permissions. It’s one of the most common mistakes that leads to supply chain compromises.

Use the regular pull_request trigger instead, which restricts forks to read-only access and no secrets. You might even consider disabling workflows from running on forked repositories entirely, depending on your security posture.

Webhooks and GitHub Apps

If you want additional security, consider using GitHub Apps or webhooks to trigger external systems instead of embedding deployment logic directly in your workflows. You can use these components to detect new repositories, analyze settings changes, or review commits for unexpected modifications (such as a new workflow in a pull request). Based on these events, you can trigger alerts or apply settings changes (such as disabling workflows) before any malicious code can execute.

Bringing it all together

Security isn’t about any single perfect defense. It’s about layering multiple controls so that when one fails, others catch the attack. Against Shai-Hulud, my defense looked like this:

- Disabled package scripts caught the attack at the earliest stage, preventing malicious code execution during package installation

- Dev container isolation limited what an attacker could access even if they somehow got code running

- Signed commits prevented unauthorized changes from entering my codebase and notified me of attempts to create commits

- Pull request workflows created a final checkpoint for catching malicious changes before they reached my main branch

These aren’t exotic security measures. They’re practical configurations you can implement in an afternoon. The key is making them your default rather than something you add only to sensitive projects. In addition, using a dotfiles repository ensures your settings follow you everywhere – local machines, cloud environments, and GitHub Codespaces.

What’s next

This is just the beginning of securing your development workflow. There are many additional steps you can take, such as:

- Using software bill of materials (SBOM) tools to track dependencies

- Enabling npm audit signatures to validate package attestations

- Configuring security scanning in your CI/CD pipeline

- Reviewing dependency updates before applying them

If you’re just starting your security journey, the four layers I’ve outlined can protect you from a wide range of supply chain attacks. They worked for me against Shai-Hulud, and they can work for you against whatever comes next.