Most developers use git merge regularly, but have you ever stopped to think about what’s actually happening when you run that command? Understanding the mechanics behind Git merges can help you make better decisions about when to merge, rebase, or use other strategies – and more importantly, it helps you troubleshoot when things go wrong.

In this post, I’ll walk you through how Git handles merges at a fundamental level, starting with a quick refresher on Git’s object model, then exploring the different types of merges and how Git decides what to do in each case.

Key structure of Git objects

To quickly recap, Git stores data as a series of content-addressable objects:

- Commits are the foundation

- Each commit in Git represents a complete snapshot of your repository at a point in time. It includes metadata (author, date, message), a reference to one or more parent commits, and a pointer to a tree object that represents the file hierarchy.

- Branches are just pointers

- A branch in Git is simply a pointer to a specific commit – the “tip” of that line of development. There’s no container, no database of branch-specific history. Just a SHA. During the life of the branch, the pointer moves forward with each new commit.

- History is commit-based, not branch-based

- Git walks history by following parent commit references. It doesn’t know about “branch history” because there is no such thing. There’s only commit history. A branch is always just a commit pointing to a tree.

- Branches are meant to be short-lived

- Git expects branches to be created frequently, used briefly, and deleted after merging. When you delete a branch, the commits it pointed to remain in the DAG (assuming they’re reachable from another branch), but there’s no record that the branch ever existed.

- Tags are long-lived

- Tags are similar to branches in that they’re pointers to commits, but they’re intended to be permanent references (e.g., for releases). They are still just a pointer (like a branch), but they can be stored as entities with messages and signatures. The pointer itself is generally a fixed value.

What happens during a merge

When you merge in Git, you’re creating a new commit (called a merge commit) that has two parents: one from each branch being merged. This is how Git represents the fact that two lines of development have come together.

The merge commit preserves the parallel history – you can see that development happened in parallel. But here’s the crucial difference: Git doesn’t record why the merge happened, which branch the changes came from by name, or maintain any ongoing tracking. It just points to the parent commits.

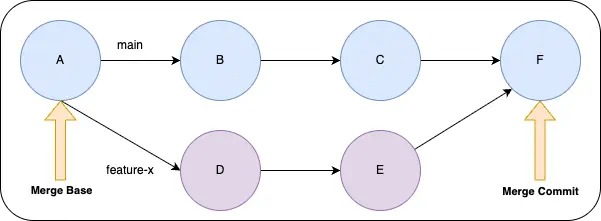

Let’s explore how this works with a simple example. In this case, we’ve merged the branch feature-x into main. Git created a new commit F that points to both D and E as parents. The graph still shows that D and E were developed in parallel, but there’s no record of the branch names (feature-x or main) stored in the commit. The commit simply indicates that F has two parents. As long as the branch feature-x exists, you can imply that branch was merged into main.

If you delete the feature-x branch after merging, the commits remain in the history (they’re reachable through the merge commit), but there’s no record that a branch called “feature-x” ever existed. The commits are just part of the graph now.

The merge process

To create the merge, Git uses the DAG. At its simplest, it walks the parents of the commits in feature-x and main to find the most recent common ancestor (in this case, commit A). This is called the merge base. Notice that it’s not a pointer or reference. It’s just a point in the graph where the two branches point to a common ancestor. This is the point where the branches diverged.

Git then compares the changes made in feature-x since C and the changes made in main since C. It creates a commit that combines these changes, called a merge commit. The characteristic shape is why this is sometimes called a diamond merge.

If neither side changes the same lines in the same files, Git can automatically combine the changes into a new tree. If there are conflicts (both branches changed the same lines in the same files), Git will ask you to resolve them manually before completing the merge.

Notice that this process doesn’t notice or care about branch names. It only cares about commits and their relationships. When the merge is complete, the main branch points to the new merge commit, while the original branch is unmodified.

Fast-forward merge

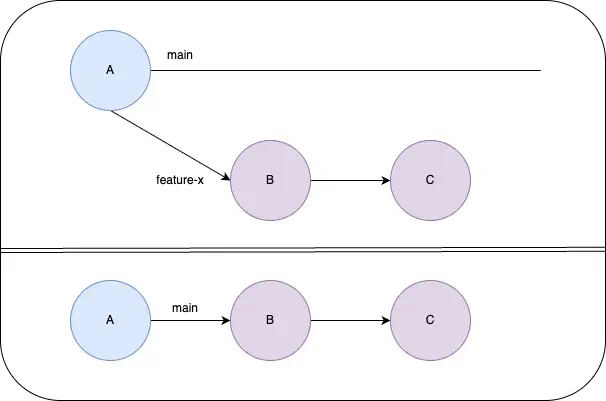

There are other options for merging as well. For example, you can do a “fast-forward” merge if the target branch hasn’t had any changes. In this case, rather than create a merge commit, Git simply moves the pointer of the target branch to point to the latest commit of the source branch. This effectively makes it look like the changes were made sequentially on the same branch, creating a linear history. Since there’s no divergence, it appears as if both branches share common history.

Rebases

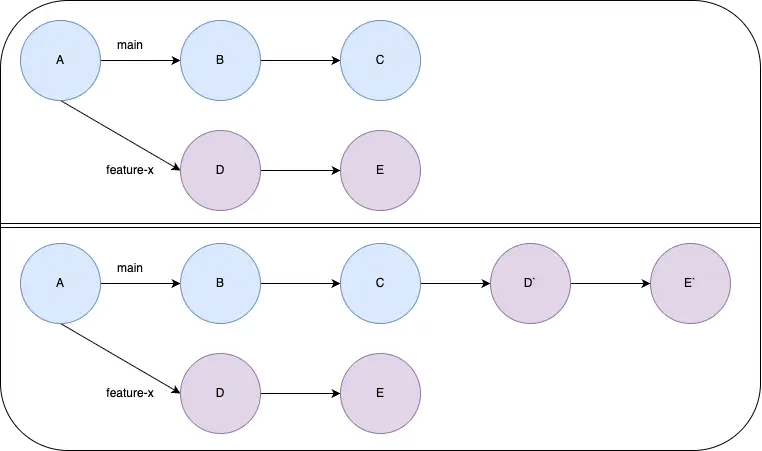

You can also rebase the changes, where they are reapplied on top of the target branch. In these cases, the commit history is rewritten to apply the changes from each commit to the target branch. This essentially rewrites the history to appear as if the changes were made sequentially on the target branch. They just start after the latest commit on the target branch. In this case, the original commits have completely different SHAs since they pointed to different parents. When the branch is deleted, there’s no longer anything pointing to those original commits, so they will eventually be pruned and garbage collected.

What about cherry-picks?

When you cherry-pick a commit in Git, you’re not creating any link to the original commit. Instead, Git will:

- Create a diff between the original commit and its immediate parent

- Apply that diff to create a new commit on your current branch

- Optionally, include a message in the commit that mentions the original commit SHA and the cherry-pick operation.

The resulting commit might have a message that says “(cherry picked from commit abc123)”, but this is just a convention, not a tracked relationship. This is why cherry-picks can lead to duplicate commits in the history if the same changes are later merged from the original branch. Git has no built-in way to recognize that the cherry-picked commit is related to the original commit beyond the commit message. Instead, it just sees another set of changes that need to be applied to create the merge (and that the changes seem to affect the same lines of code).

Key takeaways

Understanding how Git merges work under the hood gives you a clearer mental model for working with branches and history. Here’s what to remember:

- Merges create connections, not containers

- A merge commit simply points to two parent commits. There’s no special “merge history” – just the commit graph.

- Branch names are ephemeral

- Once a branch is deleted, there’s no record it existed. The commits remain, but the name is gone.

- Fast-forwards keep history linear

- Git can “fast-forward” commit by simply moving the branch pointer forward. This creates a linear history and can hide parallel development.

- Rebases rewrite history

- Unlike merges, rebases create entirely new commits with different SHAs, making the history appear linear. This hides the parallel development and creates changes that are disconnected from the original commits.

- Cherry-picks have no memory

- When you cherry-pick, Git doesn’t track the relationship to the original commit – it’s essentially just applying the changes directly

Hopefully, this helps you understand how merges work and why branches don’t really “contain” history. It also helps you see the ways that the “history” in a branch can potentially be erased or preserved as a commit graph. Armed with this knowledge, you can make more informed decisions about your branching strategy and better understand what’s happening when you run those everyday Git commands.