Have you ever migrated a repository from Perforce to Git and wondered where all the branch history went? Perhaps you expected to see a beautiful graph showing when branches were created, what was merged between them, and the complete integration history – only to find a confusing mess or a flattened linear history. Even using powerful tools like

git-p4 doesn’t fully solve this problem.

This isn’t a bug in the migration tool. It’s a fundamental difference in how centralized version control systems (CVCS) like Perforce and distributed systems like Git think about branches. Understanding this difference will help you set realistic expectations for migrations and better appreciate what Git offers in return.

How Perforce thinks about branches

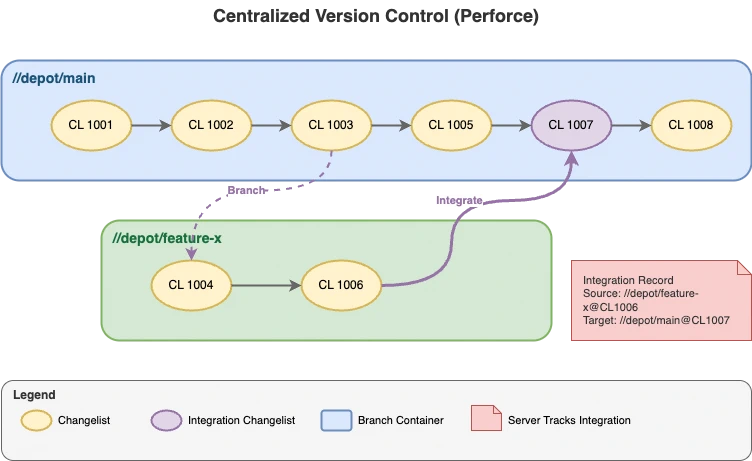

In Perforce and similar centralized systems, branches are first-class entities with their own distinct histories. Think of a branch as a container – almost like a folder – that holds its own sequence of changes. Each branch maintains its own timeline, and the server meticulously tracks everything that happens within it. To illustrate this, consider the following diagram (which is a simplification):

Here’s how it works in Perforce:

- Branches are containers

- Each branch and stream is an entity that references file revisions. There are specific database tables that track these objects, and additional tables that track the files, their versions, their relationships, and even their deletion.

- Changelists track changes

- When you submit changes in Perforce, they’re grouped into a changelist. These changelists are recorded in the server’s database, along with metadata like who made the change, when, and the affected files (pointing to both the file and a specific revision). It even tracks the specific change action, such as added, modified, deleted, moved, integrated, branched, or archived.

- The server tracks integrations

- When you merge (or “integrate” in Perforce terminology) changes from one branch to another, the server creates a record that stores the source file (and branch), destination file (and branch), and which changelists were involved. This process makes it possible to query how changes in individual files have flowed between branches over time. This also points to the files and their specific revisions, which is crucial for also tracking any changes to the files that were needed to resolve conflicts during the integration.

The key insight here is that Perforce maintains a database that tracks the relationships. For those that are curious, they also document

the schema. When you ask “what changes from feature-x have been merged to main?”, Perforce can answer precisely because it has tracked every change and its relationships as distinct, queryable record. By having this explicit tracking, Perforce can reconstruct branch and file histories and most of the relationships between them.

This has some simplifications, but it helps you to understand the nature of the entities involved. Most centralized version control systems (including TFS) have similar concepts, even if the implementation details differ. This model has several strengths, including the ability to efficiently track relationships and massive numbers of files. Since this is server-centric and database-driven, the data can be optimized with indexes and materialized views. This also improves the speed for querying the files that should be visible for a given branch or stream.

Why migration loses this information

As you may recall from the previous article, Git doesn’t have branches as first-class entities. Instead, branches are simply pointers to commits. The commit graph is the only source of truth for history, and it only tracks parent-child relationships between commits. As a result, there’s no place to store the integration records that Perforce (or other centralized version control systems) maintain.

While tools like git-p4 can try to maintain the branch names using Git branches, you can see that it’s really not the same thing. The branch names in Git are just pointers to commits that are meant to be short-lived. In the world of Git, there is no concept of mapping the flow of changes between branches. There’s just the relationships between commits.

This can be even more confusing for cherry picks or partial merges. In Perforce, these are tracked as distinct integration records, but in Git, they’re just commits that happen to apply changes from another commit. If you’re trying to synchronize the data, a cherry-pick in Git is a commit that applies a diff; it has no relationship to the original commit beyond the content.

Migrations from a CVCS face an impossible task: they need to represent a rich history of branches, merges, and integrations using Git’s commit-centric model. Since Git simply doesn’t have a place to store this information, it inevitably gets lost. While the tools can use some tricks to mimic some of the behaviors (like preserving branch names as branches), other relationships and records simply cannot be represented.

Here’s what typically gets lost:

- Branch creation history

- Git doesn’t track when or from what a branch was created. You can sometimes infer this from the commit graph, but there’s no explicit record.

- Integration records

- There’s no Git equivalent to Perforce’s integration database. Even if you migrate branches as Git branches, the record of “these changelists were integrated from branch A to branch B” doesn’t exist. In addition, Git doesn’t have a way to track changelists or partial merges of changelists. While a commit can represent a set of changes, it isn’t quite the same.

- Cherry-pick tracking

- Any partial integrations or cherry-picks in Perforce may be disconnected commits in Git. Without the integration record, there’s no way to directly relate the changes.

- Custom views/workspaces

- Git doesn’t create composable workspaces or let you compose a working directory based on specific file or folder versions. Remember, it only understands commits and those map to a complete repository state. That said, you can use sparse checkouts to limit the files in the working directory, shallow checkouts to limit history depth, and worktrees to allow multiple commits to be checked out simultaneously.

Some migration tools try to preserve some of this information by converting branches to Git branches and creating merge commits where integrations occurred. This can help preserve the visual history in a graph view, but it’s important to understand this is not a queryable relationship and the underlying semantics are very different.

Setting realistic expectations

If you’re planning a migration from Perforce (or another CVCS) to Git, here are a few things you should expect:

- Branch names may be preserved (if they still exist), but they are just a name and a pointer, not a historical record. Branches in Git are very different. In fact, if you’re using it correctly you should expect developers to be creating branches frequently and deleting them after merging.

- The overall shape of history can be preserved if the migration tool creates merge commits for integrations, but you won’t be able to query “what was integrated from where” the way you could in Perforce.

- Commit messages are often the preferred way of reflecting details about a commit, including details like the origin of the changes.

- There is no database in Git that you can query. Git relies on a commit graph and specific conventions. Metadata is stored in Git objects, which might also include the binary data of the object itself. This is one reason Git Large File Storage (LFS) is popular for large files. It allows Git to avoid storing large binary data directly in the repository while tracking the metadata and pointers to the files themselves.

- Folders and branches don’t have histories, only commits do. This is a big shift in thinking for teams used to CVCS systems.

- Git is not a general purpose file storage system. It’s optimized for source code control, which means the design assumes primarily text files that change incrementally. While Git can store binary files, it is not designed to handle large binary assets efficiently (and LFS may be required).

- Git stores the full state of the repository at each commit. It references every file and directory, even for a single file change. As a result, wide and deep mono repositories can lead to performance issues. Techniques like sparse checkouts, shallow clones, and submodules can help. Ultimately, it’s a design difference that can strongly influence your repository structure.

Training is critical

If you’re migrating a team from Perforce to Git, don’t underestimate the importance of training. The technical migration is only half the battle – the real challenge is helping your team adapt to a fundamentally different mental model. I have not seen a single migration succeed without significant training to help developers understand how Git works and why it is different.

Developers who have worked with Perforce for years have deeply ingrained habits and expectations. They expect to query integration history, rely on branch containers to organize work, and use changelists as units of work. When they move to Git and find these concepts missing or transformed, it can be frustrating and disorienting.

Here are some key areas to focus on:

- Branching strategy

- Help your team understand that Git branches are cheap and temporary. Encourage frequent branching and merging, and establish clear conventions for branch naming and lifecycle. Short-lived branches should be preferred.

- Commit hygiene

- Since Git doesn’t track integrations the way Perforce does, commit messages become even more important. Train your team to write descriptive messages that capture the context and intent of changes.

- Understanding the graph

- Invest time in teaching developers how to read and navigate Git’s commit graph. Tools like

git log --graph, GitLens, or graphical Git clients can help visualize history in ways that feel more familiar.

- New workflows

- Introduce modern Git workflows like feature branching, pull requests, and code reviews. These practices leverage Git’s strengths and can actually improve collaboration compared to Perforce workflows.

- Letting go of old expectations

- Perhaps most importantly, help your team accept that some Perforce capabilities simply don’t exist in Git. Instead of trying to replicate the old system, focus on the new capabilities Git provides.

The teams that succeed with Git migrations are the ones that embrace the change rather than fight it. Training isn’t just about learning commands – it’s about shifting mindsets.

It’s just different

Understanding these differences doesn’t make Git worse than Perforce – they’re just different tools with different design philosophies. Git’s distributed, commit-centric model is incredibly powerful for modern development workflows. It also makes the database engine portable across systems and storage containers. At the same time, it genuinely cannot represent certain concepts that are fundamental to centralized version control systems.

The next time someone asks why their Perforce branch history disappeared in Git, you’ll be able to explain: it’s not missing – it never had a place to exist in Git’s model. And that’s okay, because Git offers a different (and for many workflows, better) way of thinking about version control.